Congratulations on the publication of your new book: Changing Times. It’s not what I’d describe as your run-of-the-mill testing book. By which I mean, it doesn’t seem like it’s really targeted at testers exactly… Was this a conscious decision on your part? Why, and if not testers (or developers) – who is the book targeted at?

Thank you! It’s great to finally get it published after a long time writing and going through the process of reviewing and editing.

Although, as you rightly say, it isn’t targeted specifically at testers, I think it is fair to say that it is primarily for people involved in technology work. This could include anyone who plays a part, from an initial idea, through design, coding, testing, implementation, support, maintenance and enhancement. There are definitely subjects which will be of interest to testers and hopefully some new ways of generating testing ideas.

One thing I really wanted to do was to make the book accessible to people outside technology work too. I thought about friends and family whose interest in technology only really extends as far as using it to get things done, so I set out to write a human story which people could relate to and to use this as a way of talking about technology work.

I think I just felt particularly motivated to write about quality and the effect of technology in people’s day-to-day lives. I still love writing about testing and maybe in the future I will write a testing book!

Get TestRail FREE for 30 days!

I really enjoyed reading Kim’s story and related strongly to many of her experiences. In particular her bus journey brought to mind my own travels through the London rail and underground systems. It’s just one of a great many examples highlighted in your book. How did you come up with them all?

The stories and examples are mostly based on my own experiences or those of people around me. I’ve noticed that there are loads of conversations about technology – and to me, conversations about quality – going on. People will talk about why some company’s website is frustrating to them or why they love a particular app on their phone. These kind of conversations were a rich source of ideas!

Sometimes just observing people’s reactions in certain situations, like the one you mention when an electronic ticketing system fails, was a good way to think about how technology affects people. Simple human responses to the products people use can tell us a lot, and I found that by paying attention to my own responses I could come up with many more ideas.

I also found that as I developed Kim’s character and story, I started to discover ways that technology would more directly affect her. I previously had no idea, for example, that journalists were having some of the same debates and discussions as testers do about automation and the future of their work. It was fascinating to research the world of newspapers and journalism and to use that to come up with some of the examples in the book.

While I’m on the subject of Kim, using her story to illustrate the key ideas in your text seems to work very well. One of the key takeaways from the book for me was that the ability to identify, flesh out and use personas to help identify quality criteria (or more simply, to empathise with the end user) can be an extremely valuable skill on product development teams; but it’s not one that comes naturally to me or — I suspect — many others. Clearly you have developed some skill in this area. Can you give the rest of us some tips on how to do so?

Mixing fiction and nonfiction is an unusual approach so I’m really happy to hear that it worked for you as a reader. I’ve been really pleased by the response to using a story to drive the ideas in the book.

As you say, Kim is effectively a persona for many of the different quality aspects the book covers. Writing about a character allowed me to really immerse myself in that person’s life and think about how they would feel or respond to certain situations. I think this kind of immersion is a great way to develop empathy. Finding ways to spend time with some of the people who may actually use a product is ideal.

One of the examples in the book relates to a team of developers who worked on a system used by people in a call centre. The developers spent a couple of days with these colleagues, watching how they really used the system, what they liked and how they worked around anything they didn’t like. The support team for this particular application saw a huge change in the weeks and months after this – far fewer problems logged and far greater satisfaction from the call centre staff. The developers had taken what they had learned and made changes which improved the product for their colleagues.

I would also recommend spending a little time learning about Customer Experience and thinking about how technology fits into customer journeys. If you work with usability specialists, learning some of their techniques and observing their methods can be really useful too. I was lucky enough to work with some experts in this field at AccessHQ here in Sydney, and learned about things like eye-tracking which helped me see things from a different perspective (excuse the pun).

Another thing I often try is to think of people I know with different levels of technical awareness or ability and how they would respond to a product. For example, my parents are perhaps not as aware of technology as I am, but they still need to use it day to day. I also watch how my young kids learn to use devices and apps etc. For testers, I think it can be really helpful to look at things like the ‘7 Principles of Universal Design’ and think about the needs of different people.

Can you tell us a bit about your background? Are you still testing? How did you get into the field? What or who are the major influences on your career?

I’ve been working in software development since 1995 and almost all of that time I’ve been involved with testing. Initially I worked for a smallish company developing software for use in manufacturing and logistics. They brought me in as a graduate and needed more testers so I started out learning about testing, but I also got involved in implementation, support and training. We had clients all over the world so although our offices were in the UK, I spent time working in France, Holland, the USA and Brazil, which was a wonderful experience.

For many years I worked primarily in Financial Services and Banking – often very formal environments for testing – gradually making my way through what was then quite an established career path: tester, lead, manager and eventually managing testing across big programmes. I broke things up a bit with some roles away from the financial sector including some time in retail for the clothing company SuperDry, another role I really enjoyed.

Then in 2012 I had the opportunity to move to Australia and to take up a Principal Consultant role with Access Testing (as they were then known). It was really rewarding work, helping clients from lots of different industries and domains to solve problems. The other great aspect of the job was sharing ideas with, and learning from, some real experts in different fields, notably the Usability team I mentioned before but also Performance, Accessibility, Security and others.

During my time with the company, we changed to AccessHQ. The HQ stands for Human Quality and we spent a lot of time talking about what quality really means to people. Obviously this was a huge influence on the book and many of the ideas covered. The discussions and the people at AccessHQ also had a deep influence on my outlook.

Some of the other big influences on my career include colleagues and mentors, but also now people in the testing community. Tapping into the community of bloggers and people on Twitter is one of the best things I have done. I’ve now met quite a few people from the community at meetups, conferences and other places, and I feel so glad that I have. A wonderful group of people with incredible knowledge, but also welcoming and helpful.

My current role with IAG is more advisory and strategic. I still like to explore the products we work on and I work closely with testers and keep in touch with trends, ideas and tools in testing as much as I can, but it’s probably fair to say that I don’t do as much testing as I used to.

Facts and figures might not convey real experiences but hearing people’s stories connects us to them. Their feelings and emotions foster empathy, and help us to understand their responses. … The connection which stories can create helps us to address the empathy gap which can occur when one party is unable to understand how another party might feel in a given set of circumstances.

Join 34,000 subscribers and receive carefully researched and popular article on software testing and QA. Top resources on becoming a better tester, learning new tools and building a team.

Can you tell us about your experiences of gathering the stories used in your book? Do you have any hints and tips for the rest of us who struggle, both with the notion of collecting and also communicating user stories effectively, during the course of our day-to-day quality and testing related work?

Empathy is a big theme in the book and in the chapter you mention [in the quote above] I talk about my experiences in learning about History, and specifically watching the documentary series ‘World at War’ which uses interviews with people who lived through the Second World War. It’s a brilliant series, quite old now (even older than me) and it really demonstrates the power of people’s stories. Another example I have used in talks about Empathy is the interviews with the American soldiers who were portrayed in the series ‘Band of Brothers’. It isn’t unusual to see these interviews bring people to tears.

Stories about technology might not reduce us to tears in the same way (although the website for LinkedIn gives it a good go) but listening to people’s experiences can be really valuable. Stories don’t have to be extreme or even unusual to be worth noting – patterns can emerge which tell us something about the behaviour of a product and people’s emotional responses. If testers work in teams, it can be really useful to get together and just have a chat about subjective opinions on the product being tested.

I guess another tip is to try to pick up stories and responses about other products. If colleagues, friends and family talk about things they like or don’t like or good or bad experiences with the technology they use these can become testing ideas for products we work on.

Communicating these more subjective findings isn’t always easy and I totally understand how easy it can be to slip into the warm comforting embrace of numbers, graphs and charts, especially when managers are asking for them. The best advice I can give is to build relationships with the people who need information from testers. I’ve always found it is much easier to tell a story by talking to someone over a coffee, or by inviting them to take a look at a product with you. Effective reporting of information is a real skill and takes practise. I wish we would talk about this more in testing.

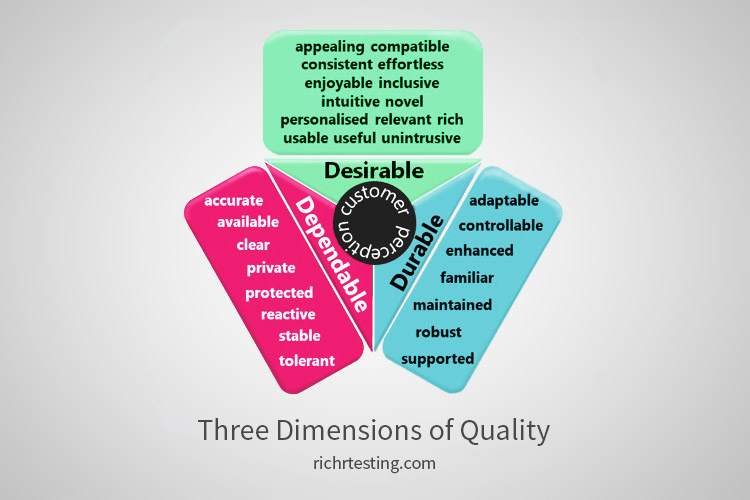

When and how did you come up with your Three Dimensions of Quality model? What inspired it?

One thing that constantly irks me is the use of the terms ‘Functional’ and ‘Non-Functional’. I wrote (ranted?) about it in a blog post called ‘Does it really work?’ a while back. I also had a bit of a rant on Twitter about it and my old friend and former colleague Matt Robson quite reasonably asked “Great, but what should we use instead?” I realised I needed a better answer for that.

So the model is partly an answer to that question. I also wanted something that was bit more human. The kind of words that we might use with friends and relatives rather than when we talk to a solution architect (with apologies to my architect colleagues). Instead of dividing the attributes of a product into functional and non-functional criteria, or focusing solely on technical criteria, I wondered if we could consider quality from a human perspective. What are the factors that affect how people perceive the products we work on?

I framed the quality aspects around the three dimensions of Desirable, Dependable and Durable. I suppose it is fairly obvious that the use of these ‘D’ words is a play on three dimensions / 3D, but I think they are all really important factors in the relationship between people and technology.

Over the last year or so I’ve been refining the list of quality aspects that appears in the book, but I certainly don’t present it as a definitive list of quality criteria – how can it be when we all have such different views on what quality means to us? I hope people can add their own ideas, suggest new words which tie to the three dimensions.

To provide people with something which they value and trust, something which will serve them well over time, we must think quality in, not as an ingredient in our product’s recipe, but as a consideration throughout the many different tasks and activities which affect it.

How do you think the model can be used to help people working of development teams to “think quality in”?

A few people have asked me about this phrase “Think Quality In” and in an interview recently it was described as ‘provocative’. I didn’t intend for it to be antagonistic but I can see why it could be interpreted that way as it is clearly a reaction to “Build Quality In”. Every time I hear “Build Quality In” I picture this building site with sacks of cement and sacks of ‘quality’ next to them and this idea that quality is some sort of ingredient to be added. I know that’s not what was intended by the phrase and there are good intentions behind it but there you go.

So to paraphrase the book, I’m saying that if we care about quality we can’t just add some magic ingredient. We have to think (and talk) about it at every stage of a product’s life, and this means thinking (and talking) about how the product will affect the real people it is intended to help.

The model fits into this along the way. As an example, I have used the dimensions and quality aspects during Inception Risk Workshops, talking to technical and business people about the purpose of a product and how relevant the quality aspects might be to the people who end up using it.

Depending on the risks identified, more focus can be given to particular elements of the design and build. If it is important that the product is novel, let’s come up with some features that really differentiate it. If it is more important that it is familiar then let’s make sure we keep the look and feel in line with other products, and so on.

I really hope that testers will use some of the words to influence their testing charters or test ideas too. If risks have been identified which might affect a customer or colleague’s experience, then spending time exploring these risks from a human perspective seems like a great idea to me.

Rich is a consultant based in Sydney, Australia. He is dedicated to improving the quality of software and providing people with technology which enriches their lives and helps them to do the things they want to do. With a background in software development and especially testing, Rich has worked on products for clients in the UK, Europe and Australia. He is an occasional public speaker, but a frequent writer and has recently published his first book, ‘Changing Times: Quality for Humans in a Digital Age’. Rich can be found on Twitter @richrtesting and at his website richrtesting.com